At Time in the nineteen-fifties, the entry-level job for writers was a column called Miscellany. Filled with one-sentence oddities culled from newspapers and the wire services, Miscellany ran down its third of a page like a ladder, each wee story with its own title—traditionally, and almost invariably, a pun. Writers did not long endure there, and were not meant to, but just after I showed up a hiring freeze shut the door behind me, and I wrote Miscellany for a year and a half. That came to roughly a thousand one-sentence stories, a thousand puns.

I am going to illustrate this with one, and only one, example. A person riding a bicycle on a street in Detroit fell asleep at the handlebars. My title was “Two Tired.”

If a writer were ever to look back on many decades of pun-free prose, Miscellany was a good place to be when you were young. Words are too easy to play on. When I joined The New Yorker, in 1965, I left puns behind. Not that I have never suffered a relapse. In the nineteen-seventies, I turned in a manuscript containing a pun so fetid I can’t remember it. My editor then was Robert Bingham, who said, “We should take that out.”

The dialogue that followed became part of a remembrance of him (he died in 1982):

I said, “A person has a right to make a pun once in a while, and even to be a little coarse.” He said, “The line is not on the level of the rest of the piece and therefore seems out of place.” I said, “That may be, but I want it in there.” He said, “Very well. It’s your piece.” Next day, he said, “I think I ought to tell you I haven’t changed my mind about that. It’s an unfortunate line.” I said, “Listen, Bobby. We discussed that. It’s funny. I want to use it. If I’m embarrassing anybody, I’m embarrassing myself.” He said, “O.K. I just work here.” The day after that, I came in and said to him, “That joke. Let’s take that out. I think that ought to come out.” “Very well,” he said, with no hint of triumph in his eye.

Robert Bingham was my editor for sixteen years. William Shawn, after editing my first two pieces himself, turned me over to Bingham very soon after Bingham came to The New Yorker from The Reporter, where he had been the managing editor. I was a commuter, and worked more at home than at the magazine. I had not met, seen, or even heard of Bingham when Shawn gave him the manuscript of a forty-thousand-word piece of mine called “Oranges.”

A year earlier, I had asked Mr. Shawn if he thought oranges would be a good subject for a piece of nonfiction writing. In his soft, ferric voice, he said, “Oh.” After a pause, he said, “Oh, yes.” And that was all he said. But it was enough. As a “staff writer,” I was basically an unsalaried freelancer, and I left soon for Florida on his nickel. Why oranges? There was a machine in Pennsylvania Station that cut and squeezed them. I stopped there as routinely as an animal at a salt lick. Across the winter months, I thought I noticed a change in the color of the juice, light to deep, and I had also seen an ad somewhere that showed what appeared to be four identical oranges, although each had a different name. My intention in Florida was to find out why, and write a piece that would probably be short for New Yorker nonfiction of that day—something under ten thousand words. In Polk County, at Lake Alfred, though, I happened into the University of Florida’s Citrus Experiment Station, five buildings isolated within vast surrounding groves. Several dozen people in those buildings had Ph.D.s in oranges, and there was a citrus library of a hundred thousand titles—scientific papers, mainly, and doctoral dissertations, and six thousand books. Then and there, my project magnified. Back home, and many months later, I sent in the manuscript. Mr. Shawn accepted it, indicating gently that it might need a little squeezing itself before publication.

Mr. Shawn seems to have instructed Mr. Bingham to hunt for a few galleys’ worth of information and throw the rest away. At any rate, what reached me in New Jersey was more than shocking, let me tell you. The envelope was large but thinner than a postcard. After glancing through Bingham’s condensation, I called the office, asked if I could see Mr. Shawn, got on a train, and went to the city. Shawn was even smaller than I am, which is getting down there, but after going past his moats and entering his presence you were looking across a desk at an intimidating sovereign. Pathetically, I blurted out, “Mr. Bingham has removed eighty-five per cent of what I wrote?”

Shawn (incredulous, innocent, saucer-eyed): “He has?”

I responded affirmatively.

He said perhaps I should have a conversation with Mr. Bingham. He would arrange it. Mary Painter, his quiet Cerberus, would be in touch with me.

Five days later, I returned to the city to meet Mr. Bingham. I remember hating him as I drank my juice in Penn Station. In Florida, in orange-juice-concentrate plants, there was a machine, made by the Food Machinery Corporation, called the short-form extractor. I thought of Bingham as the short-form extractor, and would call him that from time to time for years. He came down the hall to an office I had at the magazine, in a row of writers’ tiny spaces that one writer called Sleepy Hollow. This man who came through my doorway was agreeable-looking, actually handsome, with a bright-blue gaze, an oscillating bow tie, curly light-brown hair, and a sincere mustache—an instantly likable guy if the instant had not been this one. He said he was not sure how to begin our conversation, but he wondered if I would prefer to add things back to the proof that was sent to me or start with the original manuscript and talk about what might be left out.

He talked with me for five days. Enough of the manuscript was restored to make a serial publication that ran in two issues, but by no means all of it was restored. Citrus is citrus first and Sweet Orange of Valencia or Washington Navel second. The sex life of citrus is spectacular. Plant a lime seed and up comes a kumquat, or, with equal odds, a Seville orange, not to mention a rough lemon or a tangerine. “Character Differences in Seedlings of the Persian Lime” was the title of the scientific paper that described all that—a perfect title for anyone’s seven-hundred-page family history, and one item among many that expanded my manuscript to the size it reached as themes spread into related themes.

Writing is selection. Just to start a piece of writing you have to choose one word and only one from more than a million in the language. Now keep going. What is your next word? Your next sentence, paragraph, section, chapter? Your next ball of fact. You select what goes in and you decide what stays out. At base you have only one criterion: If something interests you, it goes in—if not, it stays out. That’s a crude way to assess things, but it’s all you’ve got. Forget market research. Never market-research your writing. Write on subjects in which you have enough interest on your own to see you through all the stops, starts, hesitations, and other impediments along the way.

Ideally, a piece of writing should grow to whatever length is sustained by its selected material—that much and no more. Many, if not most, of my projects have begun as ideas for The New Yorker’s section called The Talk of the Town, and many of them have grown to greater length. In the nineteen-seventies, observing the trials of an experimental aircraft, I intended at first to tell the story in a thousand words, but the tests and trials increased in number, changed, went on for years; a rich stream of characters happened through the scene; and the unfolding story had a natural structure analogous to a dramatic plot. The ultimate piece ran at fifty-five thousand words in three consecutive issues of the magazine. “Oranges,” seven years earlier, had grown in the same way, but my aptitude for selection needed growing, too. Bingham, after restoring much of what he had cut (and suggesting to Shawn that what we were doing made sense), insisted that substantial amounts of text remain down and out. Even I could see that for magazine purposes he was right. Four or five months later, as the piece was being prepared for publication as a book, I asked my close friend Mr. Bingham to help me choose from the original manuscript what else to restore, and what not to restore, to the text. In other words, the library at the Citrus Experiment Station had beguiled me so much—not to mention the citrus scientists, the growers, the rich kings of juice concentration—that I lost the advantage of what is left out.

Anne Fadiman, whose 1997 book, “The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures,” won the National Book Critics Circle Award and is a demonstration of the potentialities of nonfiction writing, teaches her craft at Yale. Some years ago, she e-mailed various writers she knew asking each if he or she would answer just a single question if it was asked by one of her students. Who could refuse that? I have been writing replies to her students ever since, most recently to Minami Funakoshi, whose question had to do with my book “The Pine Barrens” and a couple of people in a tarpaper shanty. Minami said, “You have many quotes in the story that capture Fred and Bill’s voices and personalities as well. Some of my favourites are: ‘Come in. Come in. Come on the hell in’ and ‘I didn’t paper this year. . . . For the last couple months, I’ve had sinus.’ I was curious—do you know right away when you hear a quote you want to include in the story, or do you usually mine for it through your notes?”

Dear Minami—Across my years as a writer and a writing teacher, I have been asked myriad questions about the reporting and compositional process but not before now this basic one of yours. And the answer comes forth without a moment’s contemplation: I know right away when I hear a quote I’ll want to include in the story. . . . In interviews, I scribble and scribble, gathering impressions, observations, information, and quotes, but not altogether mindlessly. Writing is selection. From the first word of the first sentence in an actual composition, the writer is choosing, selecting, and deciding (most importantly) what to leave out. In a broader, less efficient way, that is what goes on during the scribbling of interview notes. I jot down everything that strikes me as having any potentiality whatever to be useful in the future composition, and since I am learning on the job and don’t know what the piece will be like, I scoop up, say, ten times as much stuff as I’ll ultimately use. But when Fred Brown says “Come in. Come in. Come on the hell in,” I come in, sit down, and soon jot the line. I don’t have to be Nostradamus to sense that his form of greeting will be useful, any more than I could resist his remark about papering and his sinuses. Factual writing is also a kind of treasure hunt, and when the nuggets come along you know what they are. They often provide beginnings and endings, even titles. In interior Alaska, non-native people often describe one another in terms of when they “came into the country.” That phrase is repeated so much it is almost a litany, and I heard it so often that I had a title for “Coming Into the Country” long before any of it was written. That was lucky and rare, because titles are usually very hard to choose.

Among the three or four dozen pieces that Woody Allen has contributed to The New Yorker, the first one seemed to his editor, Roger Angell, to contain an overabundance of funny lines. He told Allen that even if the jokes were individually hilarious they tended cumulatively to diminish the net effect. He said he thought the humor would be improved if Allen were to leave some of them out.

Sculptors address the deletion of material in their own analogous way. Michelangelo: “The more the marble wastes, the more the statue grows.” Michelangelo: “Every block of stone has a statue inside it, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” Michelangelo, loosely, as we can imagine him with six tons of Carrara marble, a mallet, a point chisel, a pitching tool, a tooth chisel, a claw chisel, rasps, rifflers, and a bush hammer: “I’m just taking away what doesn’t belong there.”

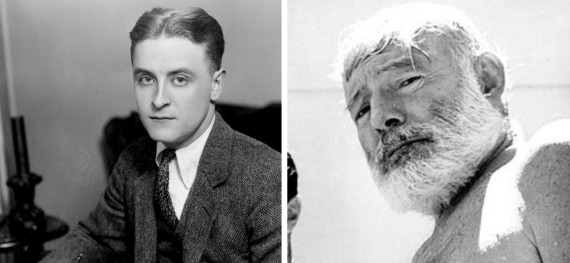

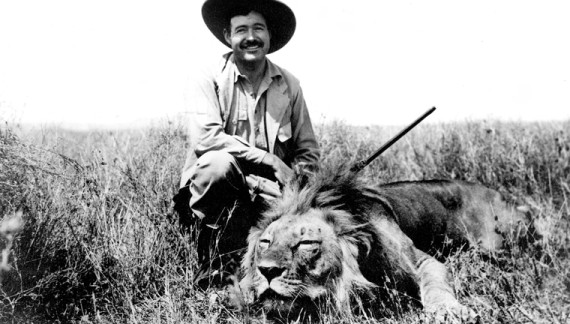

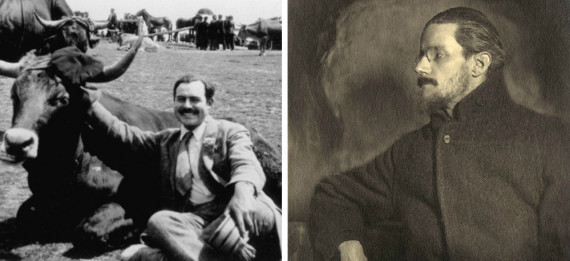

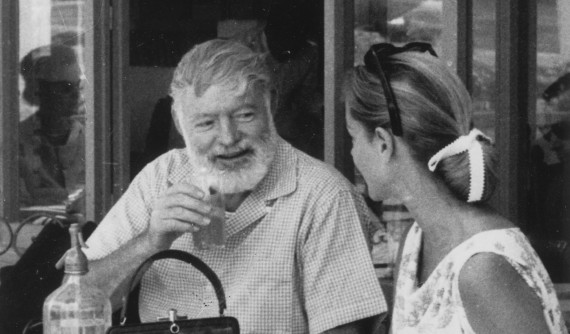

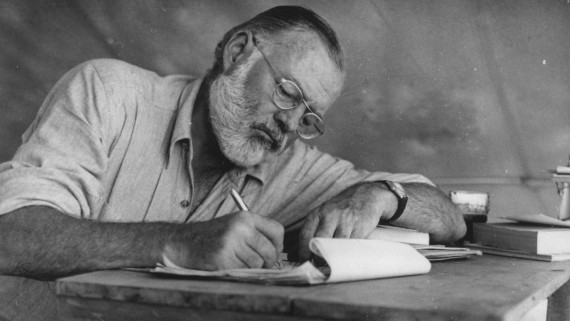

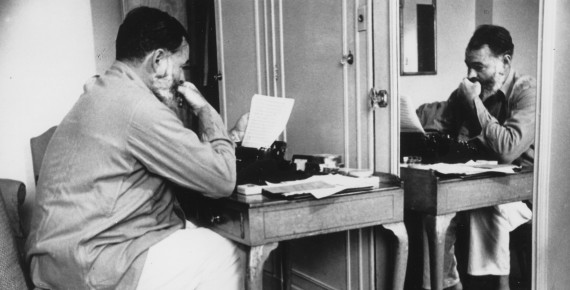

And inevitably we have come to Ernest Hemingway and the tip of the iceberg—or, how to fashion critical theory from one of the world’s most venerable clichés. “If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.” The two sentences are from “Death in the Afternoon,” a nonfiction book (1932). They apply as readily to fiction. Hemingway sometimes called the concept the Theory of Omission. In 1958, in an “Art of Fiction” interview for The Paris Review, he said to George Plimpton, “Anything you know you can eliminate and it only strengthens your iceberg.” To illustrate, he said, “I’ve seen the marlin mate and know about that. So I leave that out. I’ve seen a school (or pod) of more than fifty sperm whales in that same stretch of water and once harpooned one nearly sixty feet in length and lost him. So I left that out. All the stories I know from the fishing village I leave out. But the knowledge is what makes the underwater part of the iceberg.”

In other words:

There are known knowns—there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

Yes, the influence of Ernest Hemingway evidently extended to the Pentagon.

Be that as it might not be, Ernest Hemingway’s Theory of Omission seems to me to be saying to writers, “Back off. Let the reader do the creating.” To cause a reader to see in her mind’s eye an entire autumnal landscape, for example, a writer needs to deliver only a few words and images—such as corn shocks, pheasants, and an early frost. The creative writer leaves white space between chapters or segments of chapters. The creative reader silently articulates the unwritten thought that is present in the white space. Let the reader have the experience. Leave judgment in the eye of the beholder. When you are deciding what to leave out, begin with the author. If you see yourself prancing around between subject and reader, get lost. Give elbow room to the creative reader. In other words, to the extent that this is all about you, leave that out.

Creative nonfiction is a term that is currently having its day. When I was in college, anyone who put those two words together would have been looked on as a comedian or a fool. Today, Creative Nonfiction is the name of the college course I teach. Same college. Required to give the course a title, I named it for a quarterly edited and published by Lee Gutkind, then at the University of Pittsburgh. The title asks an obvious question: What is creative about nonfiction? It takes a whole semester to try to answer that, but here are a few points: The creativity lies in what you choose to write about, how you go about doing it, the arrangement through which you present things, the skill and the touch with which you describe people and succeed in developing them as characters, the rhythms of your prose, the integrity of the composition, the anatomy of the piece (does it get up and walk around on its own?), the extent to which you see and tell the story that exists in your material, and so forth. Creative nonfiction is not making something up but making the most of what you have.

When I worked at Time, after at last escaping Miscellany I wrote for five years in a back-of-the-book section called Show Business. In a typical week, the section consisted of three or four short pieces probably averaging nine hundred words. After you finished a piece, it entered the system in a pneumatic tube. When you next saw it, it bore the initials of your senior editor. It also had his [sic] revisions on it. You left your cubicle, paper in hand, went to the senior editor’s office, and, in a mealy way, complained. Revisions might ensue. The piece then went to the managing editor, whose initials usually joined the senior editor’s without ado, but not always. At last, with both sets of initials intact, the piece went to a department called Makeup, whose personnel could have worked as floral arrangers, because Time in those days, unlike its rival Newsweek, never assigned a given length but waited for the finished story before fitting it into the magazine.

After four days of preparation and writing—after routinely staying up almost all night on the fourth night—and after tailoring your stories past the requests, demands, fine tips, and incomprehensible suggestions of the M.E. and your senior editor, you came in on Day 5 and were greeted by galleys from Makeup with notes on them that said “Green 5” or “Green 8” or “Green 15” or some such, telling you to condense the text by that number of lines or the piece would not fit in the magazine. You were supposed to use a green pencil so Makeup would know what could be put back, if it came to that. I can’t remember it coming to that.

Groan as much as you liked, you had to green nearly all your pieces, and greening was a craft in itself—studying your completed and approved product, your “finished” piece, to see what could be left out. In fifty years, The New Yorker’s makeup department has asked me only once to remove some lines so a piece would fit. The New Yorker has the flexibility of spot drawings to include or leave out, and cartoons of varying and variable dimensions, and poems that can be there or not be there. Things fit, even if some things have to wait a week or two, or six months. Greening has stayed with me, though, because for four decades I have inflicted it on my college writing students, handing them nine or ten swatches of photocopied prose, each marked “Green 3” or “Green 4” or whatever.

Green 4 does not mean lop off four lines at the bottom, I tell them. The idea is to remove words in such a manner that no one would notice that anything has been removed. Easier with some writers than with others. It’s as if you were removing freight cars here and there in order to shorten a train—or pruning bits and pieces of a plant for reasons of aesthetics or plant pathology, not to mention size. Do not do violence to the author’s tone, manner, nature, style, thumbprint. Measure cumulatively the fragments you remove and see how many lines would be gone if the prose were reformatted. If you kill a widow, you pick up a whole line.

I give them thirty-two lines of Joseph Conrad “going up that river . . . like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings.” Green 3, if you dare. I give them Thomas McGuane’s ode to the tarpon as grand piano (twenty lines, Green 3), Irving Stone’s passionate declaration of his love of stone (nine lines, Green 1), Philip Roth’s character Lonoff the novelist describing the metronomic boredom of the writing process in prose that metronomically repeats itself to make its point (try greening that), twenty-five lines, Green 3. I ask them to look up the first three pieces they have written for the course, to choose the one they preferred working on, then green ten per cent. And I give them the whole of the Gettysburg Address (twenty-five lines, Green 3). Memorization and familiarity have made that difficult, yes, but scarcely impossible. For example, if you green the latter part of sentence 9 and the first part of sentence 10, you can attach the head of 9 to the long tail of 10 and pick up twenty-four words, nine per cent of Abraham Lincoln’s famously compact composition:

9. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here

10. to the great task remaining before us . . .

At Time, Calvin Trillin was a colleague, as he has been throughout my years with The New Yorker. In a piece for The New Yorker’s Web site, he wrote about his own memories of greening and the lessons it imparted:

I don’t have any interest in word games—I don’t think I’ve ever done a crossword or played Scrabble—but I found greening a thoroughly enjoyable puzzle. I was surprised that what I had thought of as a tightly constructed seventy-line story—a story so tightly constructed that it had resisted the inclusion of that maddening leftover fact—was unharmed, or even improved, by greening ten per cent of it. The greening I did in Time Edit convinced me that just about any piece I write could be improved if, when it was supposedly ready to hand in, I looked in the mirror and said sternly to myself “Green fourteen” or “Green eight.” And one of these days I’m going to begin doing that.

Aaron Shekey, an app designer out of Dane County, Wisconsin—a rock composer and bandleader, too—works in Minneapolis now, but is more than evidently nostalgic for the arresting silhouette of his boyhood city. Madison, the Wisconsin capital, stands on a morainal isthmus between two glacial lakes, which are not small. The hotels, office buildings, and apartment complexes of central Madison rise no more than a hundred and ninety feet, forming an accordant skyline. On his Web site, not long ago, Shekey described it in a short essay, called “It’s What You Leave Out.” Only the dome of the capitol of Wisconsin projects above all other structures. It’s like El Greco’s Toledo but without the exaggeration. It’s as striking as Mont-Saint-Michel. How has that come to be? In 1915, while the building was under construction, the City of Madison decreed that no new structure could rise higher than the base of the dome and the Corinthian columns of the capitol’s façade. No variance has ever been granted. The scene is spectacular across water. Shekey the musician closes with a quote from the script of the movie “Almost Famous”: “It’s not what you put into it. It’s what you leave out. . . . Yeah, that’s rock n’ roll.”

Or, in the words of the literary critic Harold Bloom, writing on Shakespeare: “Increasingly in his work, what he leaves out becomes much more important than what he puts in, and so he takes literature beyond its limits.”

When I was a sophomore in college, I went to Scarsdale, New York, a few days before Christmas to visit a roommate named Louis Marx. In the nineteen-twenties, his father—also named Louis Marx—and his uncle David Marx had founded Louis Marx and Company, maker of toys. Now, in 1950, it was, as Louis, Sr., seemed to enjoy saying, “the biggest toy company in the world—bigger than Lionel and Gilbert put together.” Having grown up making architectural structures from A.C. Gilbert Erector sets, and with Lionel O-gauge streamliners running all over my attic, I was much impressed. On various occasions in Scarsdale, I had also been much impressed by the sorts of people who dropped in at the Marx house—General Omar Bradley, for example, and General Curtis LeMay, and General Walter Bedell Smith. This was five years after the end of the Second World War, in which Omar Bradley, five stars, supervised the invasion of Germany, and Walter Bedell Smith, four stars, was the chief of staff, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, and Curtis LeMay, U.S.A.F., four stars, organized the bombing of Japan. Marx toys were inventive windup machines—little tinplate tanks, cars, fire engines, boats, a fourteen-and-a-half-inch G-man pursuit car—logoed with a large “X” over the letters “M A R.” Like his son, Louis, Jr., Louis, Sr., was a swift quipper, and I loved just listening to him talk. I had to be in New York City later on this particular day, and Louis, Sr., offered me a ride, saying that he had an errand there, too. I said goodbye to my contemporaries (I had dated one of my roommate’s sisters) and went down the driveway in a chauffeur-driven town car with his father and stepmother.

So this is the situation: Two-thirds of a century later, I am describing that ride to New York City in an article on the writing process that is focussed on the principle of leaving things out. I am with Mr. and Mrs. Monarch of Toys, whose friends a few years ago led various forms of the invasion of Europe. Do I leave that out? Help! Should I omit the lemony look on General Smith’s face the day he showed up late for lunch after his stomach was pumped? I am writing this, not reading it, and I don’t know what to retain and what to reject. The monarchical remark on being greater than the sum of Lionel and Gilbert—do I leave that out? I once saw Mr. Marx toss a broiled steak onto a rug so his bulldog could eat it. How relevant is that? Do I leave that out? Will it offend his survivors? In a recent year, his great-granddaughter was a sophomore in my college writing course. Her name was Barnett, not Marx. I did not know her beforehand, and had not even learned that my old roommate’s grandniece was at Princeton when her application for a place in the course came in. “You gave my grandmother her first kiss,” it began. How relevant is that? Should I cut that out? Mrs. Marx—Idella, stepmother of my roommate—was rumored among us Princeton sophomores of the time to be the sister of Lili St. Cyr. In the twenty-first century, in whose frame of reference is the strip dancer Lili St. Cyr? Better to exclude that? Best to exclude that Idella danced, too? This is about what you leave out, not what you take off. Writing is selection.

A glass partition separated the chauffeur from his passengers, soundproofing our conversation. Mr. Marx said the driver was new. Chauffeurs are good for about six months, he said. For two months, they are learning to work for you. Then for two months they are excellent. Then they start to steal from you, and two months later you fire them. Please! How much of this is germane? The car, meanwhile, has slid down the Hutchinson River Parkway and turned west on the Cross County Parkway and south on the Saw Mill and the Henry Hudson Parkway to the city. It exits at 125th Street and before long draws up at 60 Morningside Drive. Until this moment, I have had no idea where Mr. and Mrs. Marx are going. At 60 Morningside, Mr. Marx asks me if, before I continue on my way downtown (by subway), I would like to meet General Eisenhower.

This was President’s House, Columbia University, and Eisenhower was the eponymous resident. Inside, under a high ceiling, was a large, lighted Christmas tree, the Eisenhower family milling around. Soon after we had all been introduced, Mr. Marx and General Eisenhower moved toward an elevator that would take them to the highest of six floors, where Ike had a studio in which he painted. The purpose of Mr. Marx’s visit, it became clear, was for him to choose one of Ike’s paintings, which Ike would give him as a gift. Merry Christmas. Mrs. Marx stayed downstairs with Mrs. Eisenhower. Mr. Marx and the General told me to come along with them. The three of us ascended to the studio—a spacious attic awash in natural light. Ike had lined up half a dozen finished pictures for Mr. Marx to consider. Near them, on an easel in the center of the room, was Ike’s current project, an unfinished still-life. The subject was a square table covered with a red-checked tablecloth and a bowl of fruit—apples, plums, and pears, topped by a bunch of grapes. After studying for a time the paintings from which he was to choose, Mr. Marx said that he needed to pee. He would choose, eventually and shrewdly, a large canvas of the principal buildings of the United States Military Academy from across the parade ground. Meanwhile, Ike told him where he could find a bathroom on a lower floor. Mr. Marx went to the elevator and disappeared.

Now General Eisenhower and I were alone in his studio. What on earth to say—with those five stars in pentimento on his shoulders, me a nineteen-year-old college student. The problem was more his than mine, but for him it was not a problem. He began to talk about the red-checked tablecloth and bowl of fruit. He said that when he was growing up in Abilene, Kansas, his world was symbolized by tablecloths just like this one, and that was why this current project meant so much to him. The still-life was well along—the apples, plums, and pears deftly drawn and highlighted. Pretty much tongue-tied until now, at last I had something to ask. Despite the painting’s advanced stage, it did not include the grapes.

I said, “Why have you left out the grapes?”

Ike said, “Because they’re too Goddamned hard to paint.”

As found on:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/09/14/omission

Sosiale Netwerke